The Federal: https://youtu.be/olxR-TPKvvg?si=oRU_orhcC_sL2H2Z

I Wanted To Copy Marquez: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TamcXsfQyuA

The Artist’s Soul: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mp4O_xlrEmw

For a reading from the Taliban Cricket Club, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgKp7uPD3t4&feature=plcp

For the interview on The Taliban Cricket Club, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MgZi_7Bu3rs&feature=plcp

Click on this Link:

http://www.new-asian-writing.com/naw-interview-with-timeri-n-murari/

http://baradwajrangan.wordpress.com/2007/07/24/interview-timeri-murari/

http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2012/08/qa-timeri-murari

A Thesis On My Writings.

https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/95798The Federal

NAW Interview with Timeri N.Murari

NAW- Tell us about your literary journey. How and at what age did you start writing?

I became a writer by chance, and not by intention. I was working on a term paper in university and, as a distraction, I decided to write on my experience working through the summer in a logging camp in British Columbia. It wasn’t journalism but more an experimental style of writing and I doubted any newspaper would publish it, and set it aside. A few weeks later, re-reading, I modestly thought it had some merit. At the time, there were two newspapers I admired – The Manchester Guardian and the New York Herald Tribune. The Tribune folded and I sent my piece to the ‘Features Editor’ of the Guardian. I didn’t hear back, and figured it was rejected. So back to term papers and studies. By chance, a few weeks later, researching in library, I picked up the airmail edition of the MG, idly flicked through it and stopped. There was my piece, a full page too with a photograph of a river filled with logs, and my name in bold print. Fatal. If the MG had rejected it I would have continued my studies in history, and become a historian. Instead, I took to writing and contributed a few more stories to the MG. I was 20 then and, armed with the clippings, was hired to work as a reporter for the Kingston Whig Standard newspaper in Kingston, Ontario. I lasted six months, nurtured by the editor, and then fired when a new editor took over.

NAW-Tell us about your book, The Taliban Cricket Club. How did you get the idea for it? Did you carry out any research?

Way back in 2000, I read a very brief report in the newspaper that the Taliban announced they would promote cricket in Afghanistan and the regime, backed by the Pakistan Cricket Board, would apply for associate membership to the International Cricket Council. I thought the item surreal – Taliban? Cricket? They were contradictory, an oxymoron. The regime had banned everything –singing, dancing, keeping parakeets, clapping and even chess. The list is endless. I discovered there were two reasons why the Taliban decided on cricket. Cricket was perfect by Sharia law on the dress of a man – a covered head, long sleeved shirt and long trousers, no part of the body showing. I believe the second reason was the length of time it takes to play cricket – a day, three days, five days- and this could occupy the youth. Unemployment was, and still is, very high among the young men and cricket would keep them out of mischief for a whole day or two.

The idea nagged at me and I made a few notes on how I could use this for a story. I thought I’d throw in a tournament and that the winning team would be sent out of the country – all expenses paid – and probably never return. Great! But as no one knew how to play cricket back then in Afghanistan who’s going to teach my team of young men? A pro from England/India/Pakistan – it didn’t have any dimensions. Apart from a man teaching young men the game the novel would end up about cricket, cricket, cricket. I set the idea aside and went back to my other work when the Taliban were driven out by ISAF in 2001. When they ‘returned’ to fight ISAF, I pulled out my notes to re-think. I wanted to use cricket as a metaphor of how one should act within that games moral laws. I remembered growing up playing cricket with my sisters and female cousins in our garden and even have a niece who played for India. So, why not a young Afghan woman who learned her cricket in India, returns to Kabul when the Taliban announce this and have her teach her cousins how to play this game? Through her I could explore the life of a woman under the Taliban rule and have my cricket team as well. She became my first revolution, cricket the second. She’s a courageous woman who risks her life to teach her brother and cousins to play the game and through her I could explore not only the suppression of a woman’s life but her life style, relationships with her family, social customs, her humour and the sly rebellion. And even add in her love story. She opened many new dimensions in the possibilities of the novel, moving away from cricket which now became secondary. It became a metaphor – the moral code of the game, contrasting with the violence of the Taliban.

Once I decided write this novel, I caught a flight to Kabul. I was lucky to have a very good contact there who introduced me to many of his friends – professors, work colleagues, government officials and also many Afghan women who worked in his office. They were very eloquent about their lives during the Taliban rule, contrasting it with their present freedom to work and not having to wear the burqua. I incorporated their stories in the novel, turning fact into fiction. Of course, I also read up all I could on that history of Afghanistan before and after the Taliban rule. The novel was first published by Ecco in the US, then by Harper Collins, Canada, Allen & Unwin for UK and Australia, Aleph in India, Mercure de France in France etc.

“

NAW- Tell us about your other works.

They are very varied and hard to genre-cast. My first novel, The Marriage, an ambiguous title, was based on my experiences reporting on problems among Indian immigrants in the midlands of UK. It was the first work of fiction on the immigration experience and was a love story with a tragic ending. I followed this with a non-fiction work, The New Savages, on the racial tensions between kids in Toxteth, Liverpool. Reviewers and the press accused me of fabrication. A year later there was a race riot in Toxteth. I’ve written romantic comedies, Lovers are not People, set in London and New York, and contemporary fiction, The Arrangements of Love and The Small House, both set in Madras. I even wrote a crime novel set in New York. I had just published a semi-biographical novel, Field of Honour, set in Bangalore, and was planning to explore that theme further. But, I’d spend four months working on a television documentary on homicide detectives in the South Bronx. I was blocked by the experience and the detectives I’d met, and ended up writing The Shooter to unblock myself. I’ve also written historical works, set in India – Taj, A novel on Mughal India, published in 1985, has now been translated into 25 languages. I followed that with British history from 1900 to 1919 and my protagonist in the two part novel was Kipling’s Kim. These were The Imperial Agent and The Last Victory. I returned to semi-biography with Four Steps from Paradise, this one set in Madras. I wandered out of India to write The Taliban Cricket Club, (2012), a novel set in Kabul, and now published in eight countries. I have four non-fiction books, ranging from reportage on racial tensions in Toxteth, Liverpool, The New Savages; a young black couple trying to return home to Alabama from Boston in Goin’ Home; a memoir on an orphaned boy we cared for, My Temporary Son; to my 200 kilometre trek to the sacred mountain, Mount Kailash in Tibet, Limping to the Centre of the World. Limping, as I was recovering from a knee operation when I set out. And before I forget, a YA novel, Children of the Enchanted Jungle. I adapted my film, The Square Circle, for the stage and directed it at the Leicester Haymarket Theatre. Parminder Nagra, a wonderful actress and a person, played the main role; Rahul Bose played the Baul singer. A Madras theatre company staged three of my plays, Hey Hero, Killing Time and The Assassination of a Writer.

NAW- How different is the process of writing a book from a film? Was your artistic background of help when you began to write?

When I was writing my screenplay, The Square Circle, (Time magazine chose the film as one of the top 10 best film in 1997) I discovered a film is far more difficult a craft than writing a book. In a book you have freedom to let your characters meditate, explore their thoughts, remain silent for pages. In a film every thought, meditation must be revealed as an action -either in facial expressions, through the eyes on in physical actions. And that is difficult as you can’t write instructions to the actor, he must understand his character from just a few lines of dialogue and a hint of action. It’s the compression of thought/action that makes it so hard to write, pages of a novel must be reduced to a few minutes of screen time, even to a few seconds as the audience is always far ahead of the story line when watching a film. I had to learn to think in pictures, frames, what the audience will see first, before adding in any dialogue to accompany the action. My only background to this craft was watching hundreds of films – Hollywood, Bollywood, Satyajit Ray, Goddard, de Sica, Kurosawa, to name just a few. While in London, I had the good fortune to have two well known Hollywood producers work with me on my first screenplay. They taught me a lot. The screenplay never reached the screen, the fate of thousands of scripts.

NAW- You have worked as a journalist also. Which of the two do you find more fulfilling, fiction or journalism and why?

Each one has its strong attractions for me. I loved my life as a journalist, it trained me to listen to real people tell their stories and gave me an insight into their lives which I would never have had if I wasn’t a journalist at work, trying to tell their stories to the outside world. Fiction fulfills me as much as I explore themes, invent characters (as Graham Greene said all his fiction has some real life persons behind them) and allow my imagination to roam. Fiction allows one such liberties, journalism does not as it has to be accurate to the real person/life/event as possible.

NAW- When you are reading, do you prefer ebooks or printed paper books?

I’ve yet to read an ebook.

NAW- Who are your favourite writers?

The list is very long and varied, ranging from Dickens to Dostoevsky, Normal Mailer to Murakami. I have all Gabriel Marquez’s books, a complete collection of Shakespeare and also Raymond Chandler’s and Dashell Hammet’s. Hemingway and F Scott Fitzgerald sit side by side. A collection of R.K. Narayan Malgudi stories are also on my shelves. If a favourite, Marquez but all these writers are great talents that I admire and often read and re-read.

NAW- How do you write, in fits and starts or in one go? Take us through your writing process?

I write from 7.30 a.m to 1 p.m, six days a week, and never vary from the discipline I learned years ago. The only way to write is to write and write. That does not mean I don’t get up and wander around but during those hours I hate being disturbed. And once I start a book, I try to keep working on it until I have completed a draft. I set it aside, maybe start another, then return to it to see how it reads. Then come the many, many re-writes. I work on what I’d call a synopsis of the book, fiction or non-fiction, and try to map out the story line. I make many notes to myself. This doesn’t need to be linear, it can go back and forth in time. Once I feel I have it vaguely right – the characters, time frames, the theme, the setting – I start writing it. I know it will never remain true to what I had first imagined, characters take over their lives and re-chart their territory in the story. When I feel I’m on the final draft of a book, I print it out. I found when I read it on paper, I can see more flaws than on the screen and also a feel as to how it will look as a book.

NAW- Tell us about your other work life. What do you do when you are not writing?

When I finish my day’s work, I spend some time with my dogs – I have four Indian breed dogs – who do demand a lot of attention. They are very therapeutic, I enjoy their company. I usually read, both fiction and non-fiction, in the afternoons and then depending on the day and my partners I play tennis twice or thrice a week. On the other days, I walk very briskly in a local park for a half hour to 45 minutes, often as not with my wife. In the evenings I read, more magazines than books, if my dogs allow me to as they usually want to play or need back or tummy rubs. When I do take off, I head for wildlife reserves where I can spend a week or two away from work, emails etc and enjoy watching animals in their natural habitat. I have some great photographs.

NAW- What are your upcoming projects?

In July 2014, Aleph publishes my new novel. CHANAKYA RETURNS, covers a vast canvas of power, love, history, politics, betrayals, sex and more. It is narrated by Chanakya (370-282 BC), reincarnated in the contemporary world as the adviser to Avanti, the daughter of the head of a nameless state in India. In the course of the novel, Chanakya poses an eternal question: What shapes our lives—The Power of Love or the Love of Power? His protégée, Avanti, has to choose between love and power. The choice Avanti makes has all sorts of implications not just for herself and her dysfunctional family, but for the people of the state her family has ruled for years…

In his previous existence, the historical Chanakya was exiled from his homeland and took his revenge on the king, who was the cause of his misfortune, by defeating him in a war. He was then responsible for anointing Chandragupta as ruler of the Mauryan Empire, and advising him on every aspect of statecraft. In the novel Chanakya is acerbic, witty and ruthless, and provides the same services to Avanti. He manoeuvers that awkward young daughter of a charismatic powerful politician across the chessboard of power to become a brilliantly successful politician in her own right.

Now, I am working on the continuation of the family saga of this political dynasty

Publisher: Aleph. www.alephbookcompany.com

Scholastic India will publish my new YA novel, Axxiss and the Newton Chords, the first in the Axxiss Trilogy, later this year.

Interview in The Hindu

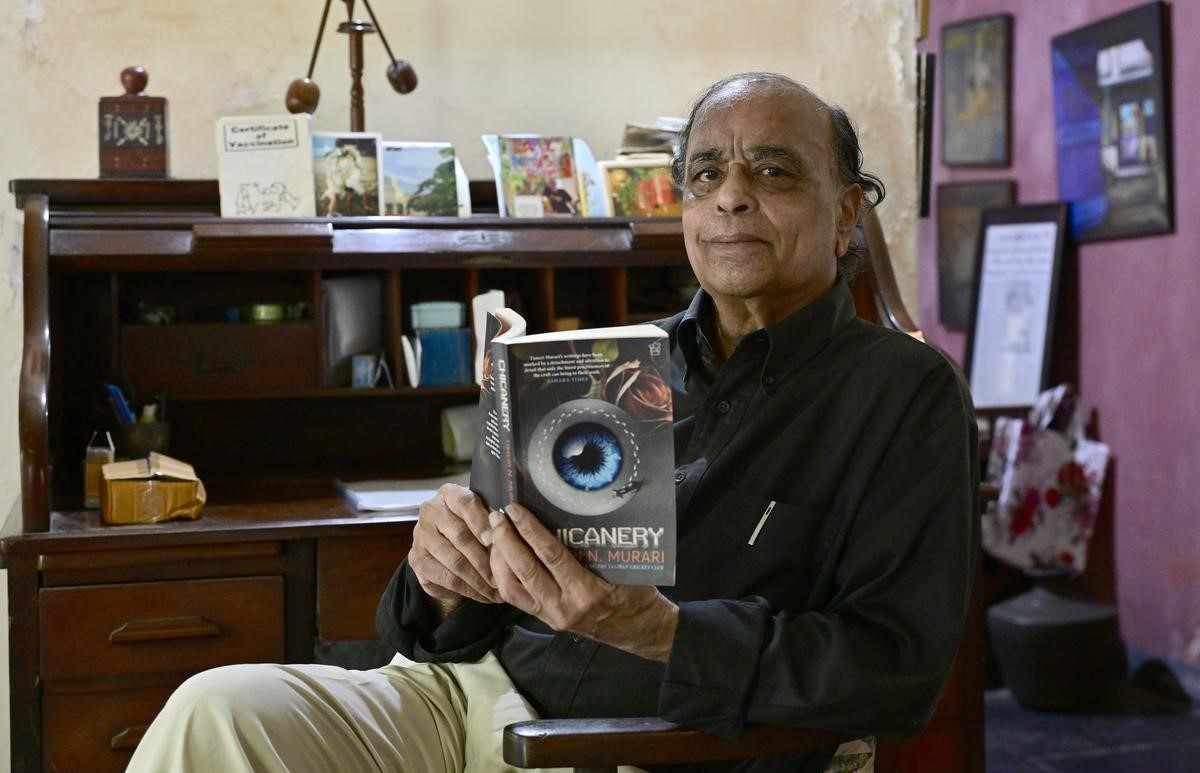

Chennai | Author Timeri Murari’s new novel Chicanery is a political thriller

In his latest novel Chicanery, Chennai-based author-journalist Timeri N Murari tells us a parable for our times

Novelist Timeri N Murari | Photo Credit: B VELANKANNI RAJ

Deep in the recesses of Devarshola, writer-journalist Timeri N Murari’s 1910-built ancestral house, is a file containing news snippets from across the decades. These tidbits squirrelled away from newspapers across the world feed Murari’s imagination years later and form the basis of his many novels. “I have a file full of ideas I’m yet to explore. Filmmaker Woody Allen used to have slips of paper he put in a draw and made a film on whatever he pulled out. When I was living in the US, I chanced upon a small news report in The New York Times of a man who knew he may be executed if he returned to his country. I tried to find out more but there was just that. The story stayed with me for nearly 40 years and found its way into Chicanery, a novel I started work on in early 2023,” says Murari, speaking above the snoring of his pet dogs in the parlour.

Released in September this year, Chicanery, published by Niyogi Books, is a story that “resonates with what is going on in the world”. It is the tale of a man who was once prime minister and then exiled, and who makes the dangerous crossing back into his country. What would prompt him to do so? A new attempt to regain power or love for the woman he left behind?

“I tried it as a stage play but it begged to be told as a larger story,” says Murari. “I was often intrigued why the man in the news report went back.”

Being in hot pursuit of the past has underlined much of Murari’s writing. Drawing from a childhood spent on the move thanks to his Army officer-father, Murari weaves his life as an old boy of Bishop Cotton’s, Bengaluru, and his career arc that took him to Canada, the UK (where he was among the first Indian journalists on Fleet Street) and the US, into the inordinate number of novels, non-fiction, plays, young adult adventures and pieces for television that he has written. Taliban Cricket Club, his book that headlines the lives of Afghanis, especially the women, is slated to be made into a film. “The interviews were done in 2010, but nothing seems to have changed for the people,” he says.

In Chicanery too, it is the women who worm their way into leading the plot. Plot-wise, the novel abides by the conventions of spy fiction and makes for a racy read. The locales have Cold War-era vibes although the story is situated in the present. “The rise of right-wing politics the world over, the cycle of democracy and dictatorship, anarchy and freedom, reflects on what I saw around me in North Korea, South America, in Spain, in Italy. Now cell-phones can change an election. I reflect on all this…” says Murari, adding why most characters do not have names in the novel. “Character names here define a concept. My main characters have names and back stories, while others in the periphery of the story, don’t.”

With a premise this compelling, plenty of plot twists, deft scene setting and language and research that is precise, the political thread running through the novel is gripping. “The story ends on a very different note from how it began. It’s not about power; it’s about the woman – therefore, his death was pointless. The woman was the protagonist! I have been thinking about a sequel,” says Murari. Including Foot Fetish, a well-known salon in these parts, is both a clever “Madras touch and a subtle personal affection. Those who know, know”.

He admits that he occasionally works on two projects at a time and reads constantly but never lets that interfere with his writing. “The draft for Chicanery took a year. I type on the computer, though I correct on a printed document. To be a writer you have to be disciplined. I write from 9am to 1pm every day; that’s the only way I’ll finish the book. On some days there is no point in pushing. I write 400-500 words, sometimes its only 100, no matter what you try. At present, I’m working on another novel set in India, a woman’s story, and on my memoirs that cover the early years of how I became a novelist, working for The Guardian and ends with the writing of Field of Honour in 1981.”

On Chanakya Returns.

CHENNAI: Have you ever thought what it would be like to have Chanakya, the renowned strategist of fourth century, reincarnate? The author of Arthashastra who helped Chandragupta Maurya rise up as the king of Maurya dynasty, is now back as our everyday politician in Timeri N Murari’s new book Chanakya Returns.

“He could be anyone, any politician you relate him to,” the author says, speaking at the launch of the book at Odyssey, Adyar. Soon, the names of Narendra Modi, Sonia Gandhi, Amit Shah and Jayalalithaa are suggested from the audience. He graciously nods to them, and repeats, “Yes, anyone!”

According to Timeri, though Chanakya is from an era of 2,000 years ago, whatever he said then is still relevant. In the book, the present day Chanakya remembers bits and pieces from his past. And to bring out a physical resemblance, the Chanakya in the book has a partly burnt face, given the Chanakya of the past is said to have been ugly. Timeri says that initially, while working on the book, Chanakya was nowhere in the scene. “But as I read my first few drafts, I realised that a character similar to Chanakya was shaping up. So I went back and read what is left of the Arthashastra today,” he recalls.

In the book, Chanakya says that people are the same today as they were 20 centuries ago. Probably, the princes and courtyards of the yore have been replaced by the rich businessmen and their bungalows. What about the stringent rules of the past, we ask. “It is said that Chanakya advised Chandragupta to cut a hand of those who were corrupt. Of course, all this cannot be done now. Most of our politicians and bureaucrats would walk one-armed then,” says Timeri with a laugh. In the book, the present day Chanakya is more like a goodwill supporter to the president’s daughter. One, who knows that the president is corrupt and does not want his daughter to follow the same path. He advises the daughter to become an able ruler and replace her dad, explains Timeri.

While there is no question that politics makes for a major part of the book, for Timeri, it was a story of a family, a dysfunctional family with politics in the background. “Just like any other family, say from a corporate world, it is a story about love and the relationship among them,” he says. However, what inspired him to write the book was the ‘dreadful situation in politics’ today. “There are so many dynasties. Every politician’s family is in politics. It’s more like a family business. Every politician’s daughter or son is in politics. It’s sort of like taking over a company,” he says with a sigh.

Known for his work Taj: A story of Mughal India and The Taliban Cricket Club, Timeri confesses to having a penchant for Indian history. “In The Imperial Agent and The Last Victory I wrote about the British period between 1900 and 1920. History has always been a favourite part of my life. It’s the stuff I like to write about,” he says. And while we await his next release, he leaves it a mystery as to whether it will be a sequel to Chanakya Returns.

On Empress of the Taj

On Enter Queen Lear

THE HINDU Sept 6/16

Timeri Murari talks about his new play and how Shakespeare’s works are still relevant today

Timeri Murari is looking forward to a trip to London next week. His new play, Enter Queen Lear, directed by Simone Vause, will open at Drayton Arms Theatre for an initial three-week run. The romantic comedy revolves around an ageing, wealthy movie star who accepts the role of Lear again, and what happens through the rehearsals. Metroplus catches up with the city-based writer to find out more.

How did Enter Queen Lear fall in place?

A friend of mine had an acting group in London that got together every week to do both old and new plays. Last October, I’d sent this play, which I had done a couple of years ago, and the actors did a reading that went off very well. My friend Nicholas, who is also my producer, wanted to give it a shot and so did the actors. I remember one elderly lady telling me how much she enjoyed the reading. I said, ‘Shakespeare must be turning in his grave.’ She sweetly said, ‘I bet he’s kicking himself for not having thought about it first.’ I was quite flattered with that remark, and that’s how it all started.

London has a terrific theatre scene, and so, casting must have been easy…

It does; it’s more vibrant than New York or any other city. The first person we zeroed in on was the lead character (Jenny Runacre) — a fine actor. The hardest part to cast was the role of a make-up artist, an Indian woman. A lot of actors would show up at the sessions and then opt out. So, finally, we found an actor who looks Indian — we were running out of time, and cast Catherine Winer to do the role of the Indian woman. I’m told she read very well and we hope she does well.

How relevant is Shakespeare today?

Well, he’s still very relevant because his works deal with human character… and that hasn’t changed at all for ten thousand years. It’s still about power, greed and love. Even now, you can do Romeo and Juliet; there are enough instances of that in India. You can stage that in a village tomorrow, and they will recognise what you’re talking about. Or Hamlet; you can see a reflection of today’s society in that as well.

Which is perhaps why even Indian filmmakers are taking it up now?

I read often about how Shakespeare’s plays are being turned into films. It’s certainly having more relevance in India. Nobody in England or America is doing movies that are set in modern times but use Shakespeare. Surprisingly, it is Indian directors who are taking them up.

You released a young-adult novel recently. How different is the process of writing that and something like Enter Queen Lear?

It works very differently. In a novel, you can have the person thinking internally for pages and pages. But you can’t do that in a play. The latter is about character and the story; you have to bring it out through gestures and dialogues. Those are the two elements for a play to work. It’s a much different craft to writing a novel, but I quite enjoy the challenges that come with it.

On Goin’ Home.

MILWAUKEE JOURNAL interview by Joy Lewis.

To the outsider, the South appears to be making good progress against racial barriers; (more jobs) are pluses. School integration and industrial growth. But, “racism has become simply more subtle– today, blacks can sit at a lunch counter but they’ve no money to buy food,” Timeri Murari said, reflecting on economic realities for many blacks in the south.

“Goin’ Home” is the story of a black family, Arthur and Alma Stanford and their young son, who attempt to resettle in Eufaula, Ala., Arthur’s hometown. After seven years in Boston, the Stanfords packed their belongings in the fall of 1978 for greener and homier pastures. They planned to build a ranch house on the acres belonging to Arthur’s father and grow their own vegetables. Alma intended to go to business school and Arthur counted on a decent paying job, paying not the $7 an hour he got in Boston spray-painting cars, but enough to support their dreams.

Murari, a 38-year-old novelist and playwright with apartments in London and New York, accompanied the Stanfords South. He is charming, with a distinctly educated British accent. Born in India, he too is dark-skinned and knows prejudice.

“In early 1978, I read a newspaper account about how blacks were returning to the south from the industrial north. In fact, black migration north had nearly stopped,” he told me. “It was quite a phenomenon. I had never been south, and I was curious.”

“I think it’s better in the south,” Arthur tells Murari in the book before leaving Boston. “There you don’t make as much but it don’t cost you as much to live and you can live more comfortable.”

Murari spent several weeks in the bosom of the Stanford clan, chatting with Odie and Bud, Arthur’s parents, tagging along when Arthur tries in vain to get a bank loan (which had been promised before he left Boston), going job hunting with Arthur, talking to Alma and other relatives, meeting civic leaders, and absorbing Eufaula’s present and past.

“A beautiful little town…like taking a journey back into the Confederate past,” he writes in “Goin’ Home.” “Everything here looks as if a deliberate attempt has been made to still time and bottle it.”

Sadly, the only job Arthur finds is at $2.65 an hour. The bank won’t loan him money unless his wife also works–dashing her hopes for business schooling. The longer Arthur and Alma stay, the more they grasp that their South and Eufaula have changed little. They learn that a dual wage system still operates–whites preferred over blacks, with more pay for the same work.

Disheartened, the Stanfords realise they can’t make it. In January 1979, they go back to Boston–defeated, they know, by racism they cannot disrupt nor escape. “I don’t think we was prepared for what stood in our paths,” Arthur says.

What frustrates the Stanfords almost as much as under-the-counter discrimination is the attitude of blacks who never left– Eufaula.

“I’ve talked to blacks who live here,” Alma confesses in the book. “And when you talk to them and tell them how far they’re set back and that things need to change, they just look at you as if you’re crazy. They say ‘You can’t change it, we’ve been like this all our lives. “‘

“You know what I found out talkin’ to the black guys at work” Arthur asks Murari. “They don’t want nothin’. They’re happy just workin’ one day to the next. The South really hasn’t changed much you know.”

“Goin’ Home” is succinct. It shows Murari’s skills as a reporter in London for The Guardian. His descriptive passages are detailed but not overburdened. Thus, the story of a realistic dream moves quickly to an inevitable fate, given the social milieu of the south. Reading the story of an ordinary black family–in their own words– and listening to white civic leaders describe and assess the “facts of life” for southern blacks and whites is an eye-opener for those who know little about southern living.

Historical accounts of the land Murari visits and the people he meets give the story fullness. Occasionally he digresses into his own terse philosophy. For instance, upon entering a down south savings and loan bank he comments: “Banks have no poetry, no prose, no songs, no dance. They always remind me of operating rooms–clean, sterile, well lit, and they bare the financial intestines of their customers. A digit here, a zero there, cleanly incised by the razor- sharp computers and adding machines. Only white people are to be seen behind the counters and in the offices.”

Murari keeps in touch with Eufaula and with Arthur and Alma who now live in Salem, New Hampshire. Alma recently finished business school and is a secretary; Arthur has an $8 an hour job in Boston. But, Arthur states in the book, he still desires to return to his roots: “One day, I’m goin’ back, goin’ home, for good.”

On Limping to the Centre of the World

“I’m not always right, but what the hell!”

Timeri Murari is a journalist by profession and writer by choice. He has authored 14 books including ‘My Temporary Son: an orphan’s journey’ and the bestseller ‘Taj’, which was translated into nine languages. In 2002, he was given the ‘R.K. Narayan Award’ for his work in cinema and theatre. He also wrote and produced the award-winning film, ‘The Square Circle’, voted as ‘one of the ten best films of the year’ by Time Magazine. The film was later adapted to theatre and staged in London to rave reviews. ‘Limping to the Centre of the World’ is his latest book about his trek to Mount Kailas. Here he is in an email interview with Ajinkya Deshmukh:

- ‘Limping to the Centre of the World’ seems like a very personal travelogue of a potently life-changing journey. How has everyday life changed after your trek to Mount Kailas?

A. The changes have been subtle, not radical, and the change continues. I have grown much calmer, I don’t worry about the minor or even major irritations in daily life; I’ve learned to pace myself and not plan far ahead. I prize every day and wake with anticipation for my work, and for the surprises that can happen. Also, I have grown far more aware of our natural world – everything from the shape of trees, the colour of leaves, the flight of birds and their calls to the changing nature of our sky. My father brought me up to be very aware of our environment and I do believe we have wounded our natural world fatally, as I’ve noted in my book. - You mentioned in the book that you are not a very religious man, and yet the journey seemed pre-ordained. How do you handle agnosticism and destiny as two very different shades of faith?

A. Yes, it is weird that no matter how hard I tried, I could not escape this journey to Kailas. Admittedly, I can’t explain this except that I went there for a child and that could have moved the mountain. Nature is power. We cannot explain the reasons for our existence, why we are born, live and die, and what our role is in this universe. Destiny does not exist; it’s not a faith in any sense. If we did have control of our destiny, individually and collectively, we’d be masters of the universe. Religion has entrapped us in a narrow set of beliefs and superstitions so we’re blinded to the wider implications of our existence on not only this planet but also in an unimaginably vast universe. Religion divides us from our common humanity.

Q. Has your belief structure undergone a revamp?

A. No, I have not, like a Paul on his way to Damascus, undergone a blinding change in belief. The trek to the mount Kailas only reinforced a belief in our natural world and its awesome power. Once man worshipped nature, now he worships himself as god. We’re helpless when nature unleashes its forces – a tsunami, an earthquake, rising sea levels, vanishing species… The dinosaurs lived longer than mankind, and yet have only left their bones and footprints, as memorials of their existence.

Q. Your works span many genres: fiction, non-fiction, theatre and cinema. Which medium of communication are you most at home with?

A. I enjoy stretching the envelope in whichever medium. It’s a challenge to always try to do something new and renew myself at the same time. In a novel the characters can internalize their thoughts and feelings while in a film we must see this happening and on the stage, hear it. An idea sometimes suggests itself as a novel, sometimes as a film and I try to follow my instincts.

I’m not always right, but what the hell!

Q. ‘The Square Circle’ won you many accolades. What is the theme of the work (film and play)?

A. I had always meant the film ‘The Square Circle’ (‘Daayra’) to be a love story between two people trapped in opposite identities. It’s an intriguing essay on the nature of real and assumed gender identities and cultural proscriptions. It’s also an exploration of sexual identity in an Indian context where love has nothing to do with marriage and sex has little to do with love. As I was unhappy with the film director’s interpretation, I re-worked it as a stage play which I directed at the Leicester Haymarket theatre. The main leads were Parminder Nagra and Rahul Bose. The theme remained the same, though not the ending. In the play, I returned to my original ending.

Q. Your travels have taken you the world over. Apart from established names, do you think India fails to provide an equal platform to budding writers and playwrights?

A. The answer is a big YES. Certainly new writers are having their works published but are given very little support by their publishers, while Indian playwrights are expected to write free of charge for amateur dramatic companies, at least in the English medium. In the West, writers and journalists are given a great deal of respect, while in India they’re looked down upon as inferior professionals.

Q. How would you comment on Indian writing in English? Any favourites? - I can’t claim to have any favourite but there is a lot of very good writing coming out of India, but also some very bad writing. Editors and reviewers appear to have problems in distinguishing between utter drivel and true talent.

Q. Departing from literature, having been a journalist, do you think Indian media, especially electronic, has steeped much into yellow journalism and sensationalizing?

A. Viewing our Indian news channels leaves me fuming and worse, uninformed. It is a very depressing experience. There’s very little hard news, no serious investigative journalism while many hours are squandered on murders, rapes, scams, movies and excessive sports. No doubt they’re of interest but India needs to be better served by this ‘new’ medium.

Q. The last few years have seen you professionally very productive. Anything new in the pipeline?

A. I’m stretching the envelope again. This time I’ve written a young adult work of fiction which will be published by Scholastic later this year. We’re still working on the title and it will appear under a pseudonym. I will also start a bi-monthly column for the New Sunday Express from November.

Q. Through a cultural perspective, what do you think lacks in the Indian psyche?

A. I wish we Indians had a better sense of humour. I don’t mean slapstick or the crude adolescent humour in cinema. I mean a sense of wit. We take ourselves and, even worse, our politicians, too seriously. After all, nature has a wicked sense of humour!

India Abroad January 2, 2004 the magazine

ENCOUNTER

Love with an English Flavor

Shobha Warrier Speaks to Timeri N Murari, whose 25-Year-old Novel is Making a Comeback in Hollywood

In 1978, when Timeri N Murari was a journalist with The Guardian, he wrote Lovers Are Not People. He had just moved from London to New York. Twenty-five years later Carlton America, the Hollywood film production company, is recreating his novel as a contemporary film.

The novel, written in the first person, is the account of a wife whose husband deserts her and their two young children for a younger woman. Instead of letting him go, the jilted wife resolves to bring him back. Playing detective, she learns he has gone to America with the young girl. She follows him to New York, befriends the girl, undermines the relationship and wins back her husband.

Murari has written the novel – a love story of disappointment, possible divorce and emotional entanglement – in the form of a romantic comedy. There is nothing Indian about his novel. The husband and wife are British and the mistress, an American. New York provides the setting, for a drama ideal for Hollywood.

“It came out of an emotional experience I had been through,” recalls Murari, 62, who in 1959, moved to London from Madras to study engineering but found his calling in writing. “I had just moved from London to New York and had been away from India for a long time. The characters came through naturally as English and American.” Since the story was the written as the woman’s first person account, Murari felt she had to be an English woman.

In 1963, after studying at a university in Montreal and freelancing for The Guardian, Murari joined a newspaper, in Kingston as a reporter. “I was very lucky to have got my first job,” he recalls. “Most papers were not willing to hire an Indian. They were very prejudiced against Asians at that time. “

In six months the new editor sacked him. “I was the only Indian in the newsroom but when I was fired, the rest of the staff was ready to go on strike against racial prejudice.” But he dissuaded them and returned London to join The Guardian.

Looking back, he feels The Guardian had perhaps published his articles unaware that an Indian wrote them. “From my name, nobody could make out my Indian identity,” he laughs. Murari feels other British journalists accepted him only because he played good cricket.

The only other Indian working with The Guardian then was cartoonist Abu Abraham, whom Murari remembers as a “very charming, friendly man, always there for you with advice.” Abraham, who died last year, once told him, ‘I would like to see people like you in India rather than your talent being used here.’

Once he left England, Murari was struck by the difference between the America of the 1970S and the England of the 1960s. “America was a more open society, and much easier to get on with because it never had colonial ties with India,” he reasons. “The British had prejudices against India because they had ruled India. There was a lot of racial prejudice there, and I wanted to escape that. “

He wrote Lovers Are Not People during his stay in New York. About four years ago, William Blaylock, a Hollywood producer and Murari’s friend, read the novel and wanted to make a film out of it. Taylor Hackford, the director of well known films like An Officer And A Gentleman, was to direct it and Murari went as far as writing a screenplay. But the project fizzled out.

“After that, I had forgotten completely about the novel and the project,” he says. “Then I got an email from William [saying] that somebody else is interested in the project and [inquiring] whether the rights were available. I said yes, and the contract was signed. “

For copyright reasons, Murari is not writing the screenplay for the new project. Scripting began in Hollywood in December. Casting is due in February and the film will be ready for release by fall.

Love, betrayal and retribution are these not ingredients for a wholesome Indian film? In fact, not

long ago, one-of Murari’s’ friends thought Lovers Are Not People was ideal for a Tamil film.

“It did not materialize,” he says. “You know the kind of films that are made [in India]. Efforts to attract Hindi film producers also did not [work]. I am happy that it is not going to be a Hindi film. Commercial elements in Hindi involve six songs, six dances, etc. At least in Hollywood, she [the wife] will not be made to dance around New York! I am happy that it is going to be a Hollywood film!”

He has his reasons to be peeved with the Hindi film industry. In his only stint with Hindi films, Daayra (1996) starring Nirmal Pandey playing a transsexual and Sonali Kulkarni, he ran into disagreements with director Amol Palekar.

“(Daayra) was the second crossover film to reach the Western audience after [Shekhar Kapur’s] Bandit Queen but it did better than Bandit Queen in France and England,” Murari recalls. “I would have loved to direct the film but I didn’t have the experience and the film financiers wanted a name known to the film field. That was how Amol Palekar came in. I gave him a full script. The film was a disappointment in one context that Palekar changed the end, which I didn’t like at all. He killed the cross dressed man in such a stupid way. But it was very satisfying in the context that all the reviews that came out barely mentioned Palekar but mentioned me, the writer, which is very rare in the film business. Time magazine voted it as one of the top ten best films of 1997 and in their review, they only mentioned me!”

To compensate for the disappointment, he directed” the same story as a play titled The Square Circle for the Leicester Haymarket theater. Murari says it was an extremely satisfying experience directing Parminder Nagra (before she became famous for Bend It Like Beckham) and Rahul Bose as the transsexual. “I thoroughly enjoyed directing the play. I had a very talented cast. Parminder’s role was a very demanding, emotional and physical role and poor Parminder had to do it night after night. In the no-minute play, she is there on stage all the time.”

His association with Hollywood is not going to end with Lovers Are Not People. Another novel, Field of Honor, set in Bangalore in 1952 “in a time when India just became independent and was changing,” might appear as a Hollywood film soon.

Since 1973, when his first book Marriage, a work of fiction set in England, was published, Murari has written over a dozen fiction and non-fiction books. He returned to Chennai in 1988 when his father fell ill and now lives there with his Australian wife.

On Steps From Paradise.

EXCERPT from THE HINDU interview by Kausilya Santhanam

Q: The themes of your novels are varied. ‘The Shooter’ deals with a New York cop, ‘Taj’ about a historical love story and ‘Steps from Paradise’ about a family in South India.

A: I don’t keep within a genre or style of writing. It did confuse my readers initially for they expect a writer to keep to type. The publishers too want you to remain on one genre. But I want to push the envelope. My novel ‘Steps from Paradise’ is in one way, a metaphor on the impact of colonialism on India. Here it happens on a much smaller scale. This is about a close knit family, like our joint families of the past, and when a stranger enters the household, it starts to fall apart. It cannot withstand the impact of this ‘invasion’. And a member of the family invites the invader in. Even as in our history, the invader has always been invited me, often as not to defeat another prince. So, it is about an inner betrayal as well.

Q: Is ‘Steps from Paradise’ autobiographical as it is set in Chennai and focuses on one particular family?

A: Of course, on the surface every novel does seem autobiographical, especially if it’s a contemporary story. Every time Graham Green published a novel, the reviewers claimed it was semi-biographical because he dealt with certain themes. Of course, I have drawn on certain characters, places and situations that existed in the Madras of those days. After all, I was born and raised in this city, so if I do write about it, it will look biographical because of the time and places. Yes, there are some parallels to my own life in the novel. My mother died when I was very young, even as the narrator, Krishna’s mother died when he was very young. And like the narrator Krishna, my father did bring in a European governess to look after my sisters, brother and me, whom he eventually married. She became our stepmother. She was a very disruptive influence in my family because she had no understanding of how our joint family functioned. I’m afraid I didn’t like her very much at all. But this, a second marriage, is something that happens in many families and I hope that readers will identify with the problems of this particular family when something so devastating as a mother’s death occurs, leaving young children. You don’t have a choice when your widowed father re-marries. So, what I was writing about below the surface was the impact of a person from an alien culture into a family situation. But there the similarities end. Krishna’s brother dies in an accident. My brother’s alive and well. Krishna’s sister marries a zamindari and leaves him. That’s fiction too. When one writes, drawing on one’s own experiences, fact and fiction become blurred and indistinct, the words become all one fabric and it’s impossible to unweave it and say ‘oh this thread is true’ but that thread is ‘fiction’. Let’s say it’s a more personal novel than any I’ve written before, although ‘Field of Honour’ also had the same theme of a family conflict.

On TAJ-A Story on Mughal India

EDINBURGH EVENING NEWS interview by John Gibson

She was 12. He was 17. And they fell madly in love. One of the greatest love stories that’s just been told. By Tim Murari in his double-edged novel “Taj.”

Half is a novel about the true-life love affair, half about the building of one of the wonders of the world, the Taj Mahal.

We’re talking about the seventeenth century, long before the Brits made it their own. Shah Jahan, the Shadow of Allah and Conqueror of the world, fell in love only once.

But permit me to tell you the love story as I heard it from Mr Murari when he brought a breath of the subcontinent to Edinburgh the other day.

Monument

“The nobleman’s daughter was always behind the veil until the one night of the year she was allowed out with the veil removed, during an annual festival. By chance the prince saw her and it was as they say love at first sight.

The Shah became the richest man in the world but all his wealth couldn’t prevent her death at 35. He ordered eight days of mourning, he lost two inches in height and his hair turned white.

“Which brings me to the second half of my book. Shah Jahan, who never remarried, commanded 28,000 men and women to labour day and night for 22 years to build the Taj Mahal -an ever-lasting monument to his one love.”

Murari now lives in London, New York and his native Madras, where at school he was taught that the Taj Mahal was designed and built by an Italian jeweller, before the education authorities set the record straight.

With “The Jewel in the Crown” and “Gandhi” re-kindling interest in India, 43-year-old former Fleet Street Journalist and TV documentary writer Murari feels the climate is “Just right” for “Taj.” But he stresses that his novel has nothing of Britain in it. It’s set exclusively in the pre-Brit period.

“India bad been there for a thousand years and you discover from the book it bad a rich culture and a lot going for it. The British only re-invented it.”

And Lord Curzon, a Brit, was largely responsible for the restoration of the Taj Mahal in 1901.

LIVERPOOL POST interview by M.W

FROM THE troubles of Toxteth to the marble splendours of the Taj Mahal is a fair leap. but ex-Liverpool resident Timeri Murari has made it.

True, he lived in the city way back in 1974 when he rented a room near the furniture store which was to go up in flames in the Toxteth riots some years later.

Tim was strategically placed to see the social problems and sense the simmerings of violence among the young blacks and whites even then.

He was gathering material for his book The New Savages; Children of the Liverpool Streets. which got good reviews even if the title did spark off some controversy.

A more glamorous spot, the Taj Mahal, is the subject of his new novel ‘. Taj.’

It is a testament to love-in more ways than one.

When Tim. who was born in Madras, took his Australian bride Maureen to see the Taj he realised how little he knew about its story. “Therefore,” he says, ‘I read all I could find about ii so I would appear more erudite in the eyes of my wife.”

Tim has dedicated “Taj” to his own lovely lady. ..Maureen.

MID-DAY (Bombay) interview by Tara Patel.

WHO IS Timeri N. Murari? I was asked to interview him at such short notice I forgot to ask him what the “T” stood for!

After all the man’s of Tamil origin and not a very remote. origin at that. Murari’s new book is titled Taj and more important, I didn’t ask him enough about the novelist’s licence, I imagine he’s taken on is love-story of Arjumand Banu, the Mumtaz-i-Mahal of our very own marble monument in Agra which lovers (of all kinds, presumably) have come to gape at for over three centuries.

It’s his eight book to date, must be the only novel of its kind-everybody well, almost- knows about the Taj Mahal and its story, never mind if the romance has been romanticised beyond historical fact, the whole world loves a lover and all that.

It’s fact that Emperor Jehangir’ son Shah Jahan fell in love with a nobleman’s 12-year-old daughter and married her-allegedly he adored her so much that in a span of 18 years or marriage she bestowed on him 14 children and, nor surprisingly, died during her last childbirth.

Hence, the Taj-it is sad, 20,000 labourers worked day and night (so we are told) for 22 years on a marble tomb to beat all other marble tombs. Some say the emperor built the Taj to boost his ego, after al! building grand buildings was a royal Moghul past- time, others less cynical say it was built purely out of an undying love for his begum as also out of guilt that she died delivering his children that’s the author’s interpretation.

In his early 40’s, Murari relates how he’d come to pick on the Taj Mahal as a subject for a novel: it seems in a previous book set in India his American and British editors wanted to put a picture of the Taj on the cover (never mind if it was only fleetingly mentioned in the book!).

“It made me so mad,” remembers Murari, “their vision of India, especially in America, is limited to the Taj Mahal. I promised to write about it in my next book if only they’d remove it from the cover of my book at that time. Once I started researching, the story became absolutely fascinating and so tragic that I got taken up by it. I’ve enjoyed writing this I book the most’.

No, not much of his research work was done in India although he’d visited the Taj several time. His father, a major in the army during his school days had a posting in Agra. But for the book, he spent a year researching and writing it at the New York Library (which in his opinion is the best in the world, on par with the British Museum Library).

On how he took to writing. After boarding school in Bangalore he went to Loyola’s in Madras, quit after a year in favour of an apprenticeship , with Marconi’s (electronics) in the UK. But after two years, he went on to McGi11 University in Montreal.

He started reporting for a small town paper in Ontario called the’ Kingston Whig-Standard. the editor. Donald Sutter, taught him the ropes of the profession; alas, a new editor proved to be racist and Murari quit, took to doing journalistic assignments on a free lance basis for the London Guardian. the Sunday Times. the Observer and other papers and writing books.

On The Arrangements of Love

NEW SUNDAY EXPRESS- Sushila Ravindranath.

What is the theme of your new novel?

THE ARRANGEMENTS OF LOVE is an intricate and subtle exploration of love. I’ve constructed a quirky and oddball scenario that reveals a tender and moving story of characters all looking for something – and hidden under these individual stories is the search for love, in its many guises. There are three main characters involved in these searches. Nikhil, an NRI, looking for his father and escaping a broken marriage. Apu, the detective he hires to find his father and who mourns for her own lost love, and the father who lives alone with the memories of a betrayed love. Love after all is the raft we all cling to in this very lonely sea we all exist it. Without it, everything else is meaningless. At the same time, the novel’s a detective story and about surviving in the chaos and confusion which is our India. Here, as we all know, we must expect the unexpected and India is full of surprises.

You’ve set this novel is Madras? Why is that?

Apart from Madras being my home city, my family having lived here for many generations, I deliberately wanted to set it in this city as it’s very seldom written about. If you look at all the novels being written today by Indian writers (or even non-Indian ones), they’re all set in a north Indian city or in a north Indian landscape. Madras barely exists in the modern literary landscape; it’s fallen off the map. Yet I find this a fascinating and exciting city. It has the subtle blend of tradition and modernity, it’s a passionate city and quietly cosmopolitan. It’s also a city with a long history and many beautiful buildings which I hope will not be demolished by our philistine government. I wrote about the city in my previous novel, STEPS FROM PARADISE (which, by the way, will be reissued by Penguin Books next year). And I set another one of my novels, FIELD OF HONOUR, in another south Indian city, Bangalore. I love the south and even in my novel ‘TAJ-A story of Mughal India’, set entirely in its historical locations, I managed to drag in a south Indian character to make him major figure in that story.

What are you working on now?

I have completed a new work of non-fiction, OUR HOUSEHOLD GOD, about my personal experiences with an orphaned baby. It’s again set in Madras (Chennai if you wish) and I’m still working on finding the right title. Penguin Books will be publishing this one early next year. I’m currently working on the final re-write of my new novel, which I’ve just completed an early draft, and you guessed right – it’s set in Madras and other south Indian locations.

TODAY. Meenakshi Reddy Madhavan

THE ARRANGEMENTS OF LOVE is so different from your earlier book, TAJ, that was released earlier this year. Which genres do you prefer- contemporary/historical fiction?

It’s not a matter of preference really. It’s how I want to tell a story. I have written two other historical novels, set in India, after Taj and at the time thoroughly enjoyed recapturing Indian history as I was then in the mood of writing and studying our history. History gave me a great perspective on our past and what I have said often is that when we study our history how little things have changed. In both Mughal and British times our conflicting self interests which allowed the invaders in divided us. And I should add that our present day politicians remind me of our princes of the past, both in their lifestyle and their lack of morality. But then contemporary fiction reflects the times we live in which is an equally exciting genre to work with and I have been writing it for the last few years.

This book deals with the whole NRI confused thing. Don’t you think it is a little clichéd?

When you say clichéd it means that what I am reflecting is our present day problems. The novel isn’t entirely about Nikhil and the NRI problems but also about the relations

my detective, Apu, has within her present, day society about love and arranged marriages. She is a modern Indian woman coming to terms with the death of a man she had loved and struggling against the family pressures most young people face in places like Chennai. The novel also deals with the break up of a marriage (Nikhil’s mother’s) and the consequences of what happened. So while it is partially about NRls, it’s about how love or the lack of it can distort our lives. And I do believe these are problems facing every one of us as we all want and need love.

Would you describe your new work, OUR HOUSEHOLD GOD, also as autobiographical?

It is, I suppose, somewhat autobiographical and is about my and my wife’s relationship with an orphaned baby. The baby was surrendered for adoption by its parents because it had a serious problem. My wife saw it in a Chennai orphanage, raised the necessary funds (over a lakh) for the nine-hour operation to correct the problem. And she arranged for its adoption abroad. But it stayed with us to recuperate and unfortunately remained in our home for a year before the adoption came through. It’s really a love story between the baby and two elderly people.

You have worked with Parminder Nagra of Bend it like Beckham (for The Square Circle where she played opposite Rahul Bose). Tell us about the experience?

Working with Parminder was great. I found that when you direct a very talented actress, your life can be both easy – because she responds so well to suggestions – and difficult because she needs to understand the motivations of the character. In my play she was on stage all the time and gave herself both emotionally and physically to the role. In fact, when I first cast her, she didn’t want the role because she knew it would very demanding. But once she agreed to play the main lead she gave herself to the role over a 100 per cent.

On the film The Square Circle

INDIAN EXPRESS interview by Mukund Padmanabhan.

TIMER N. MURARI, author of The Square Circle, defies genre, like the director who’s made his 1993 screenplay into a winner of a film. Although he’s sometimes inexplicably described as a Raj novelist, only a couple of his many books fall squarely in this category. In a sense, even the term Indo-Anglian author appears misplaced. For instance, three of his novels -which are set abroad -have no Indian reference points and are written with a completely Western sensibility. A former journalist- he worked with The Guardian in the early ’70s – Murari hasn’t been economical with his output: he’s both diverse and prodigious. In a little over two decades, he has written ten novels, two non- fictional works, three plays and a couple of screenplays that have dealt with subjects as varied as the Raj, historical romance, crime and social drama. His best-known book, of course, is Taj, the historical novel that was translated in nine European languages.

When Murari wrote The Square Circle (originally titled Stolen), he was unsuccessful in raising money for the screenplay soon after he had finished it. It was after a friend introduced him to Pravesh Sippy(he’s co-producing the film along with Murari) that the proposal to film it (using Amol Palekar as director) took shape.

A tragi-comic love story where the key characters are a young abducted and girl and a transvestite. The Square Circle may well evoke comparisons with Bandit Queen. It is transparently feminist (perhaps unwittingly anti-male) and its raw, blunt dialogue is peppered with four letter words. Like Phoolan Devi Murari’s girl seeks vengeance after being abducted and raped.

Beneath the hard and bitter carapace of The Square Circle, however, lies an underbelly of wit and tenderness. Despite its profanity and violence, Murari’s (hitherto unpublished} script appears intended not so much to shock but to undermine our notions of normality. ‘Natural’ is the love between the young girl and the transvestite; ‘abnormal’ is the malevolent, male-dominated, misogynistic society they inhabit. The script succeeds in weaving a web of empathy for the couple as their relationship-which seems founded on a shared loneliness and a sense of being unloved and unwanted -blossoms into an odd but convincing love.

The Madras-based author says he’s “90 per cent happy” with Palekar’s rendering of his screenplay and thinks that Nirmal Pandey and Sonali Kulkarni were “brilliant” in the lead roles. The residual “10 per cent” unhappiness relates mainly to the film’s end.

Murari, meanwhile, has written another screenplay. He’s reluctant to talk about, beyond saying that the story is based in Madras and that the film will constitute his next project. He has also recently sold the rights of one of his novels, Lovers Are Not People, to a Hollywood producer. His latest novel, Steps From Paradise, was published by Hodder and Stoughton earlier this year .

As executive producer, Murari was present when The Square Circle was filmed in Orissa between December 1995 and February this year. Although a low-budget film, he’s unsure how much the film will recoup financially. “I’ll be happy,” he says, “if all those who invested in this film get their money back.”

PREMIERE interview by Sara Wallace.

INDIAN WRITERS MAYBE ENJOYING acclaim on the global literary scene, but aside from Satyajit Ray, Indian filmmakers have tended to neglect international markets in favour of entertaining 90million viewers back home with popular Hindi spectaculars A rare crossover is The Square Circle, which charts the relationship between a village girl who is sold into prostitution; and the male transsexual who persuades her to live as a man.

“A film like mine would be hard pushed to gain distribution in India,” says Square Circle screenwriter Timeri Murari. ‘Bollywood is absolutely formulaic. Films have to be three hours long and contain no less than six song and dance routines. Bollywood is in such a rut, it is looking to Hollywood for inspiration rather than drawing on Indian experience.”

Despite celebrating 50 years of independence India, according to Murari, “is in a state of crisis. We’ve had 50 years of corrupt politicians, AIDS has reached epidemic proportions; infanticide of girl babies takes place on a real scale; and yet India is culturally unable to look at these problems.”

In The Square Circle, the heroine is sold into prostitution; as she travels as a man, her horizons expand. Things are slowly changing for the better for some Indian women, but on the whole life is very hard. So, what impact can a film like The Square Circle have? Murari simply hopes the reaction will be like “a stone in a pond creating a ripple effect”.

Murari is currently in production on his next film, about a racist London cop who travels to India and discovers that his own father was an Indian. It will star Indira Varma (also seen in Kama Sutra, another Indian film that opens in London this month but had a huge struggle to get Indian distribution). “I want to show the world,” says Murari, “a little piece of India that it rarely gets to see.”

The Imperial Agent Interviews

EDINBURGH EVENING NEWS interview by John Gibson

TIM Murari could be sitting on a fortune with his new novel, “The Imperial Agent.” It’s his sequel to Rudyard Kipling’s revered picture of British India early this century, “Kim,” and according to its author it would make a blockbuster movie, even more impact as a TV mini series.

Says Tim, Madras-born and now spending nine months of the year in his native India: “It’s a big adventure story, an espionage tale in fact, and with its five or six characters interwoven I feel it would do better on TV than cinema. I’ve had my ego boosted by some influential people who are suggesting it might make another’ Jewel in the Crown.’

Manipulated

“You have a Smiley character in control of Kim, still harbouring divided loyalties and love. Kim’s now 30, as opposed to the Irish boy spy Kimball O’Hara immortalised by Kipling, and we meet him at the start of the freedom movement in India. Which way is he to go? That’s what the reader has to find out. In the original story Kim was very Indian in his upbringing until he was discovered by the colonel character who trained him to spy for Britain. I’ve taken him on from there and he’s still being manipulated by the colonel, your present- day Smiley.”

Tim feels his timing with this formidable novel is pretty well ideal.

“Kipling was 50 years dead last year and host of Kipling books came out. His copyright was up last January. There’s a public who have heard of Kim and a public who haven’t heard of either Kim or Kipling, so my novel shouldn’t be hard to sell. Hollywood owns the film rights to ‘Kim’ and when they made the first film in the thirties Kim was played by an American brat and Errol Flynn played a friend of his.”

“They re-shot it a few years with Peter O’Toole as the Lama and an Indian boy cast as Kim. If they bring my novel to the screen I could visualise Harry Andrews as the colonel, but maybe Harry’s too old now. “

“I wanted to write only one novel about Kim, spanning 1905 to 1922. By the time I got to 1910 I knew I’d need another 500 pages, so it’s one novel in two parts. There’s a bit of sex in it, but Kipling said that Kim knew all kinds of evil. You couldn’t call it steamy and I’ve woven some Indian mythology into it. The book isn’t aimed at one market, it’s intended for anybody who craves a good story.

“Rather than write about somebody who’s having a nervous breakdown in suburbia, I chose Kipling’s creation.”

INDIAN EXPRESS interview by Geeta Doctor

WITH his bushy eyebrows and faded blue jeans, Timeri Murari is all set to play the part of the writer as “angry young man”.

He doesn’t flick an eyelash though, when I ask him what he feels at the normal response to his name, “Murari who?”, for certainly his work appears to be almost unknown in India. He smiles in that manner described as faintly quizzical in the best Victorian novels. He doesn’t have to justify his intriguing first name which is taken from his ancestral village just off Ranipet, near Madras, nor his work which winged on the tag ‘Best-selling’, has made its way into nine different languages. Sitting in the pale pastel, cane-and-bamboo comfort of an old Madras house, Murari waits for me to ask my next question. For Murari is first of all a journalist. After studying at McGill University, Canada, he worked for the Guardian at London and then went over to New York, where he now lives part of the time. In the USA, he started doing a series of real-life TV, documentaries based on the lives of newly arrived immigrant communities.

Murari then took to roaming the badlands of the Bronx and came up with a police detective novel: The Shooter. ‘Cops are great storytellers”, he volunteers by way of explanation. None of this, however, really goes to explain how he moved into India next and produced not only the best-seller Taj but also two books of historical fiction, that form part of the same story, that show him to be a writer of strong imaginative fibre. He cites both Norman Mailer and Gabriel Garcia Marquez as possible mentors, but turns to Kipling to borrow a hero, Kim, for his panoramic plunge into a period of Indian history, that is still the province of autobiography, (Nirad Chaudhuri’s being the latest example) and liberation theology.

‘I wanted to know more about recent events in India. A lot has been written from the point of view of the British. That was what was immediately apparent in the course of my research, …I wanted to re-create the period between 1905 and 1919 and look at it from the point of view of an Indian.

“Part of the reason that I took Kim was that I wanted a character who was very special for the British and make him eventually an Indian who would be willing to die for his country. Kim had in him all the ingredients of divided loyalties that made him very interesting for me, I wanted to open him up a bit more.”

On The Marriage

Excerpt of Hindustan Times interview by Sudhir Sonalkar.

‘How The Marriage came about was that the London Sunday Times had an investigative page called Insight,’ Timeri N. Murari explains. ‘They had a call from an Indian immigrant worked in Coventry. He told them about an extortion racket preying on the immigrants and was appealing to the Times to help them. I was then working as a freelance writer, mostly for The Guardian. I knew the Times editor, so he called me up to hire me as part of the Insight team investigating the extortion. I went up to Coventry first to check out the story and met the caller. It turned out that there were thugs among the immigrants themselves who were working the extortion. If an immigrant did not pay up, they threatened to get him fired from his job. Obviously, the local white shop stewards were taking a piece of the action as well. The person I met had reported all this to the police but the immigrants were too scared to tell the cops anything, so the cops couldn’t get any affidavits, so they couldn’t press any charges.’

The paper sent three English reporters and Timeri Murari, an Indian journalist, to look into the case. After spending some ten days with the immigrants, Murari and his friends were able to obtain two affidavits and prepare a report. On returning to London, however, they found to their dismay that the affidavits were not adequate to prevent libel action against the paper. As the report was never published, Murari was upset, and egged on by a sense of injustice, decided to transfer the whole business to fiction.

‘Obviously, the novel does not remain wholly true to the events,’ Murari said. ‘I soon found myself immersed in the broader question of looking at the Indian community in England as a whole, and of fabricating complete characters. The story line also changed, and semi-heroes and semi-villains emerged, who played their role in the unfolding drama and withdrew. But I also wanted to explore the loneliness of self-imposed exile. These immigrants had voluntarily left their homeland, yet they constantly yearned for their villages in the Punjab. At the same, I wanted to look at the problems of the second generation that had no idea about India at all. They were born in England, educated in English and, were to all intents and purposes, Englishmen and women. Would they or could they follow the old traditions and customs, including such important decisions like an arranged marriage, or would they be more British in their outlook? I wove in the love story of Leela and Roger to explore that theme.’

The New Savages Interview

LIVERPOOL POST interview by Harold Brough

TIMERI MURARI whose forth. coming book is the subject of a court injunction today, is a freelance writer who came to Liverpool in search of the human story behind urban decay and deprivation. He left with a lingering hangover of depression

It was not just the reality behind statistics about sub-standard housing or ,jobs in South Liverpool, but living with the people, the tension in their lives, the limited hope of escape.

“Yes, I was surprised by what I found.” he says. “I did not expect the tension of the boys there. I came out of it very depressed, I took some time to recover from it. I liked the boys and I felt terribly sorry for them. Their horizons are so limited by the situation.”

He spent more than two months in the area, on the street corners, around the sad, derelict buildings, the tenements, the cafes, researching for “The New Savages,” which is due to be published next month by Macmillan, unless a judge in chambers decides otherwise.

The book is about two days in the life of four fictitious but allegedly typical Liverpool boys in this part of the city. They are Marko, a 17.year-old half-caste, Ato, the white Negro unsure of his identity moving towards a breakdown, Trenchy, the white boy paying lip service to the Boot Boys while attempting to stay out of trouble, and Bicklo, leader of the Boot boys, at least temporarily while the king is in prison. Together, with their friends and their enemies, they, live their hopeless lives in a world which includes the booze, the battling and the beef (girls).

The main theme says Murari is the despair of the situation. ‘No one is going to do very much about it. The economic situation is not right to help alleviate the situation.” He says the conclusion is the despair of the four, their inability to escape their destinies.

But the book is also about deep racial tension and it also contains reported comments on life and the scene in this part of the city by several local people who for different reasons are involved with the people and the problems.

Murari served his time day and night, rain and shine researching the book with the young ones, and others to the extent of following in the wake of the flying bricks in the fight between white and coloured. He says the characters are not overdrawn. and while despair may be the main conclusion he talks of the colour tension: “There is conflict between black and white. There is a great deal of bitterness in the community.”

He is 33, single, and was born and educated at Madras. He went to university there and in Montreal, the, idea for a book about people in this type of urban environment stemmed from reading a dull, boring report-“2 1/2 people sharing 1.3 bathrooms” a report in which the people involved were hidden by statistics.

So he went in search of the people, visiting cities including Birmingham and Sheffield before deciding to base his book on Liverpool. A fight between white and coloured young people happened while he ,was staying in the community. He has no reason to think it was an isolated or particularly rare event.

But he would expect to find a similar situation of tension in other big cities. While he expects fighting to continue spasmodically in Liverpool but not at a high pitch he expects that of other cities also.

But for several reasons it was a depressing stay. One is that, if he is right it is the young who harbour these feelings. The other is his claim that fighting, once territorial, has become racial.

‘Yes it does not sound very good for the future.”

On The Shooter

INTERVIEW

Why I wrote THE SHOOTER.

It was certainly different from previous work – a novel set in India called ‘Field of Honour’. I’d spent six months researching and making a television documentary on homicide detectives for a British TV channel. These were the pre-NYPD BLUE days. The detectives I chose to film were with the 7th Homicide Zone in the 48th precinct, South Bronx of New York City. The precinct was just below the Cross-Bronx Expressway. During those months, I witnessed many homicides and murder investigations, walked down dark hallways, and raced down fire escapes with the detectives. Their streets were mean and very dangerous. I also socialised with many of them – dinners, drinks, birthday parties, fishing. By the time I’d finished I’d made three or four really good friends and had developed a great admiration for many of them. When I returned to normality and decided to write a new novel, I found myself blocked by the experience. Cops are great raconteurs with a grim sense of humour, and my head was filled with their stories. To clear the block, I wrote THE SHOOTER, and dedicated it two of the friends I’d made – Capt. John Culley and Detective Andy Lugo.

The novel after that was the best seller, set in historical India, TAJ (link to Taj), on the Taj Mahal.

On the stage play The Square Circle.

THE GUARDIAN interview by Chris Arnot.

Timeri N. Murari’s theatrical version of his controversial film, THE SQUARE CIRCLE, which might shatter a few illusions about the ‘homeland’, opens this week. Gang rape and transvestism are featured. ‘This is the real India, not the version put out by Bollywood,’ Murari says. ‘This is the India where women are casually molested and most men are male chauvinists.’

Murari has flown in from Madras, grateful to Vayu Naidu for giving him the chance to direct his work in the way that he intended, rather than the way it was treated in Bollywood. ‘She’s obviously a kindred spirit and we both know that in the theatre the writer has control,’ he says over a drink in the Haymarket bar. He’s a former journalist – a Guardian man full of entertaining stories of old Fleet Street. But he’s a serious writer too, with 10 novels to his name and a burning desire to erase the memory of director Amol Palekar’s treatment of the film.

The Script examines the relationship between an itinerant actor who dresses up as a woman and a young village girl persuaded to dress up as a man for her own protection after she had been abducted and raped. Eventually, they become lovers. Not a typical Bollywood movie, then. The miracle is that Murari managed to get it produced at all by a film industry where screen sex is usually confined to a gyrating navel in a see-through saree. ‘My script is about sexual identity,’ he says. ‘How we define ourselves as men or women and how that identity governs the way we live our lives’.

Having gone so far with it, he was appalled when Palekar changed the ending and had the transvestite hero bumped off by the same men who had raped the girl. ‘We rowed about it, but once a director gets the bit between his teeth there’s no stopping him. There was no reason for it. I can only think Palekar was disturbed by the character and wanted to take revenge on him.’

The ending that Murari envisaged will finally be revealed in the Studio at the Leicester Haymarket. You have been warned.

THE HINDU interview by Gautam Bhaskaran.

‘The Square Circle’ was neither a square nor a circle. Timeri N. Murari’s baby that it was, this original screenplay struck disaster when Amol Palekar directed it. The film had meandered away from the original and all that Murari could do was gnash his teeth in anguish rather than anger.

During a chat with Murari just before he flew to London, I was curious to know why he had, at all, thought of making a movie out of it, rather than staging it as a play first. Which is the usual practice. Murari agrees that there have been instances of a motion picture being adapted into a theatrical production. ‘Sunset Boulevard’ is a classic case of the screen slipping onto the stage.